First Avenue Estate seen from across York Avenue, the current location of the Rockefeller University campus, around 1921.

FRIENDS recently capped its weeklong series exploring the cultural and historical context of Yorkville’s City and Suburban First Avenue Estate and the decades-long battle to preserve it, which relied upon both local advocates and the legal system at our country’s highest court. This progressive residential complex was successfully saved from demolition in October 2019, after a fight that raised issues of historic preservation, urban land use, affordable housing, and the value of cultural history.

We explored those issues in a series of discussions with panelists Andrew Dolkart, Will Cook and Anthony C. Wood, joined by moderator Lisa Ackerman. The discussions focused on how the First Avenue Estate, one of the oldest extant privately-financed, limited-dividend Model Tenements in New York, helped redefine urban workers’ housing, inform the way we live now, and set a legal precedent for historic preservation on the basis of social history. At a time when our nation grapples with how we shape our historical narrative, and whose stories we tell, it feels especially prescient to consider the legacy of the fight to preserve First Avenue Estate, which Wood called, a “humble looking building with a powerful story.”

The three conversations, plus a forward-looking fourth discussion with special guests involved in the fight, were recorded and are available below. Together, the panel weaves a complex and instructive tale on preservation advocacy. Read on to learn more about that story and discover a variety of related resources.

The light-court Tenement

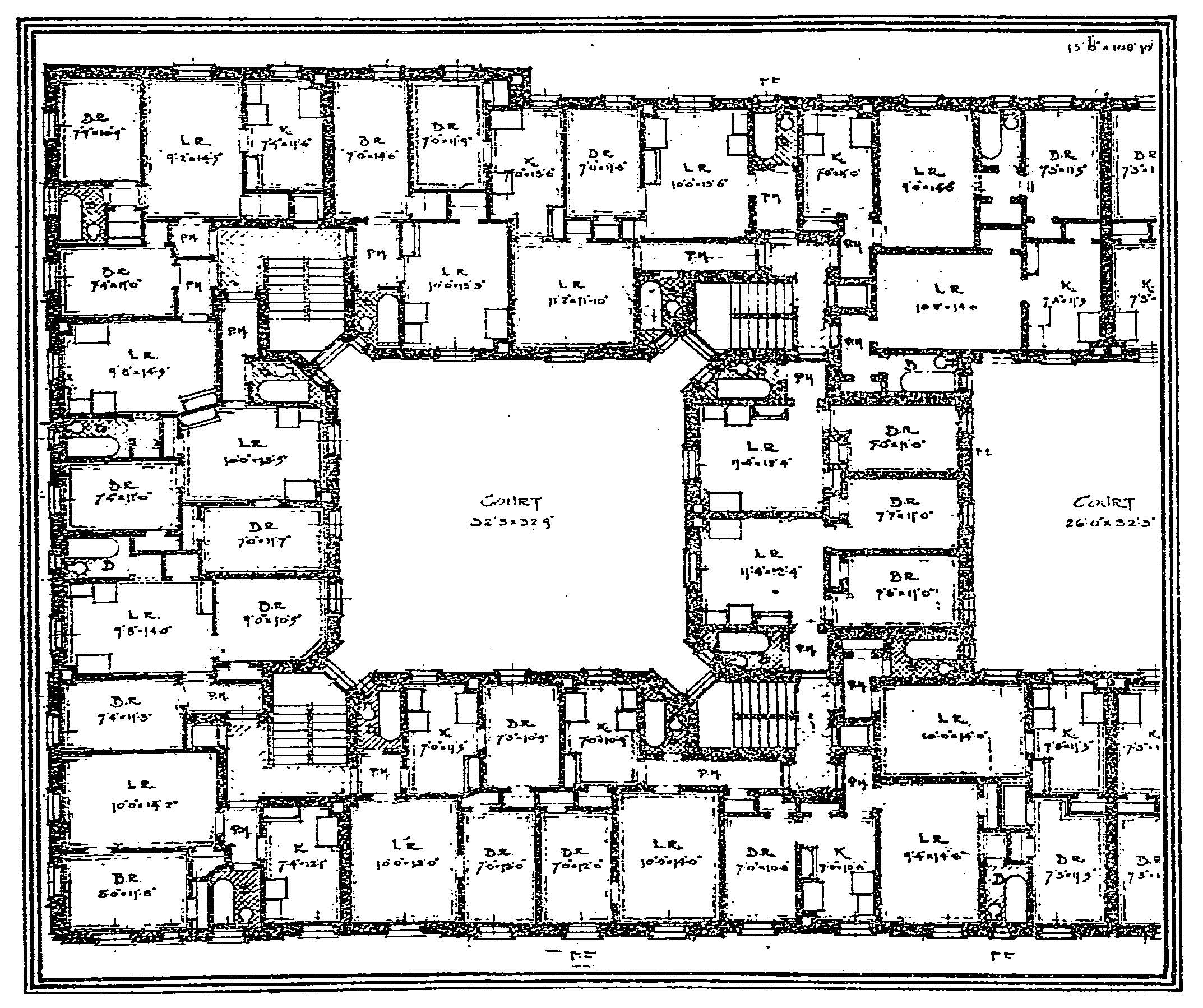

The First Avenue Estate, a multi-building complex built by the City and Suburban Homes Company between 1898 and 1915, was a pioneering experiment in workers’ housing, which endeavored to give low-income New Yorkers access to safe, clean homes. As one of the most successful privately-financed, limited-dividend Model Tenements in New York, First Avenue Estate redefined what affordable urban housing could offer. The project also inspired a variety of other complexes, including the York Avenue Estate, located nearby at 79th Street and York Avenue, also by the City and Suburban Homes Company; Hillside Homes in Williamsbridge, the Bronx; and Boulevard Gardens in Woodside, Queens.

Also in Yorkville, the City and Suburban York Avenue Estate, built between 1901 and 1913, was the largest low-income housing development in the world at the time of construction. You can find the landmarks designation report for York Avenue Estate here, and the designation report for First Avenue Estate here.

These “light-court tenements” featured interior courtyards, street views, private bathrooms, wide stairwells, and large windows, offering tenants an abundance of light and cross breezes, amenities that were virtually unheard-of in workers’ housing up to that time. Comprising 15 individual buildings, construction on the First Avenue Estate complex began in 1898 and was completed in 1915. This highly progressive project not only prefigured the nation’s first comprehensive zoning code regulating light, air and land-use (1916), but was also highly influential in the passage of the 1901 Tenement House Act. Such codes governing light and air continue to inform the way we live. For example, the requirement that all bedrooms in New York City apartments must have an exterior window stems directly from such legislation.

Interested in reading the 1901 Tenement House Act? Check it out here. For further information about tenement housing in New York City, take a look at this exceptional resource guide created by the New York Public Library, which offers photos, maps, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, archival materials, and a robust reading list – including work by Andrew Dolkart – on the history of New York’s Tenements!

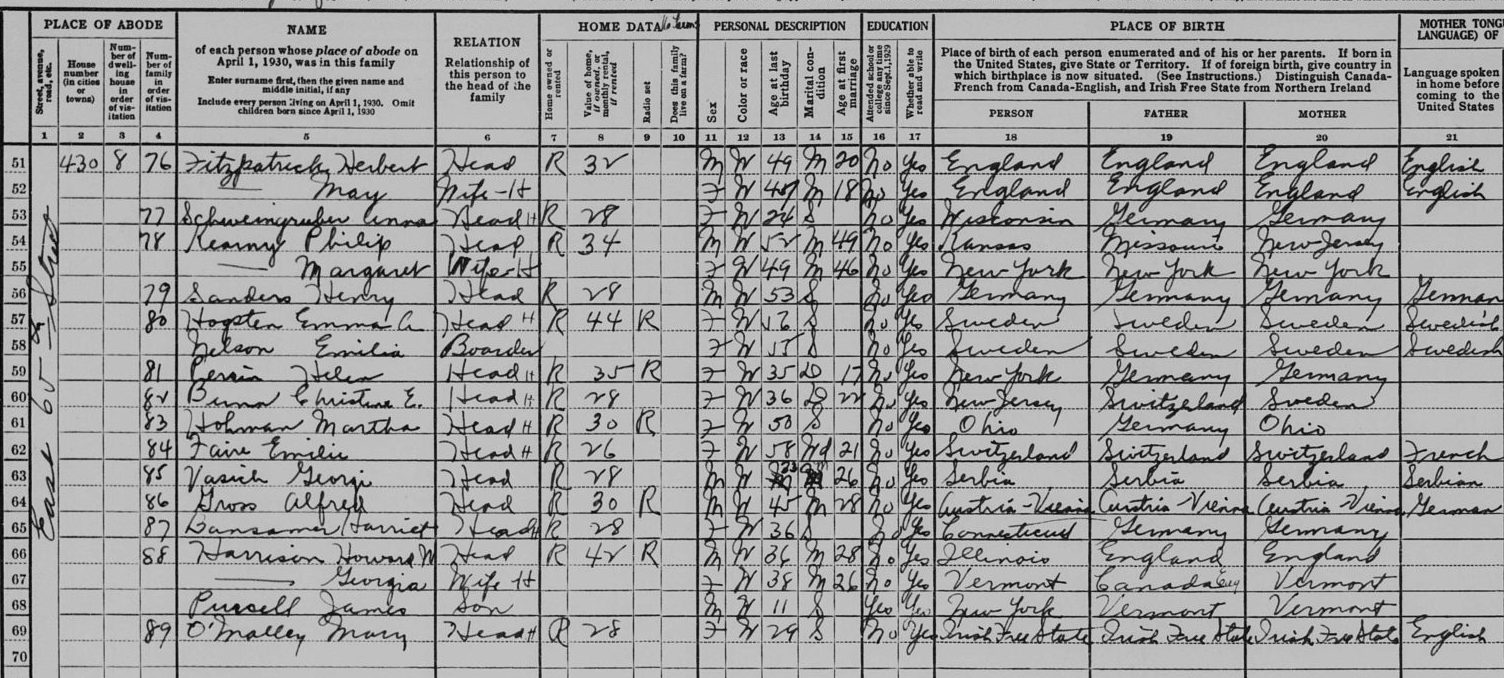

The considerable architectural reforms at First Avenue Estate made the complex a haven for a diverse immigrant population, which would have otherwise been relegated to cramped and dangerous tenements. According to the 1930 census, residents had immigrated from such countries as Serbia, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Ireland, Finland, Italy, Austria, and Yugoslavia. The complex helped make Yorkville a melting pot, and allowed people from all over the world to live with dignity as they made new lives in America.

Looking to do your own genealogical research? The National Archives offers these resources regarding every census between 1790 and 1940, and Internet Archive offers the complete collection of US Census data, 1790-1930. Still need to fill out the 2020 census? You can do it here.

The residences at First Avenue Estate were home to a low-income immigrant population, but it was not conceived or run as an act of charity. The Estate was financed by some of New York’s most illustrious families, including the Vanderbilts, the Stokes, and the Goulds who established the City and Suburban Homes Company in 1896 as a Limited-Dividend company. This meant that owners limited their profits to just 5%, whereas typical speculative builders often profited 20% on their investments. Thus the owners sought to find what the company’s president E.R.L. Gould called a “middle ground between pure philanthropy and pure business,” keeping the homes accessible to working New Yorkers while proving that well-constructed low-income housing could turn a profit. Not only could they turn a profit, Limited-Dividend housing ultimately became big business for organizations like the Russell Sage Foundation and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

For more information on Limited-Dividend Housing in New York City, check out A History of Housing in New York City, a city-wide survey by Richard Plunz, or “Progressive Housing in New York City: A Closer Look at Model Tenements and Finnish Cooperatives,” a report prepared by students in Andrew Dolkart’s Historic Preservation Graduate Studio at Columbia University.

Landmarking and Hardship

In recognition of this social and cultural significance, the entire block-long First Avenue Estate complex was designated as a New York City individual landmark site in April 1990. However, after objections by the owners, the (now disbanded) Board of Estimate voted to eliminate the two easternmost buildings along York Avenue (429 East 64th Street and 430 East 65th Street) from the designation. This action in August 1990 initiated the concerted effort to save the complex in its entirety, an objective that the owners continued to protest through a dizzying number of administrative and legal challenges for nearly 30 years, until the most recent action in October 2019 from the U.S. Supreme Court when it denied hearing the case.

The two buildings in question finally regained landmark protection in 2006, under the leadership of FRIENDS and Councilmember Jessica Lappin. By that point, the owners had stripped the buildings of much of their original architectural details and ornamentation, and covered them in pink stucco! This effort to make 429 and 430 ineligible for designation was denied by the court, and actually reinforced the fact that these buildings were designated for cultural and social significance, rather than architectural beauty.

429 East 64th Street and 430 East 65th Street in 1992.

429 East 64th Street and 430 East 65th Street. Stefano Ukmar for The New York Times.

Determined to realize the value of the East River-facing property by constructing a much larger structure, the owners Stahl York Avenue refused to accept the landmark designation and filed a hardship application with the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2010. In the application, Stahl requested an exemption from landmark status on the grounds that designation made the buildings unprofitable and therefore constituted a hardship. In 2014, the LPC once again asserted the significance of the entire complex in its unanimous denial of the hardship application. From there, Stahl filed both State and Federal lawsuits against the LPC to overturn the denial and proceed with plans to demolish the buildings. The Federal case was dismissed in 2015, with the court again upholding the LPC decision, while the State case continued to wind its way through the legal system, until the New York State Court of Appeals denied Stahl’s motion to appeal in 2018, and finally the U.S. Supreme Court denied a petition to appeal the case.

For a step by step account of the fight, check out FRIENDS' City and Suburban Timeline of Events.

The consistent upholding of the LPC’s decision to deny the hardship and protect the entire site in recognition of its cultural significance, despite Stahl’s persistent efforts to thwart the designation and even physically deface the buildings, is part of what makes this case so remarkable. Cultural significance is just one of several criteria in the New York City Landmarks Law, which also include “social, economic, political, and architectural history.” Despite this broad mandate, however, designations at the time rarely included properties that embodied these criteria.

Looking back on this long battle, the First Avenue Estate case is important from a legal perspective because the social history of the complex – as vitally important in the cultural history of low-income housing and the immigrant experience in New York City – is a constant thread in the legal argument for its designation. However, as Will Cook, an attorney who worked for the National Trust for Historic Preservation during its involvement in the case, pointed out in the panel discussion, “laws don’t amount to anything until they are tested and enforced.” Accordingly, chronicler of preservation advocacy Tony Wood explained, “the whole preservation community was activated well beyond these buildings. [The case] was now about the Landmarks Law.”

“We have to fight the good fight if we want the city to reflect the full breadth of history and all the stories that can be told.”

- Lisa Ackerman

Lisa Ackerman, acting as moderator to the discussion, noted that the inclusion of cultural landmarks in the law in 1965 was incredibly forward-looking, providing a path to preserve sites that are relevant for reasons beyond architectural significance. Recognition of such cultural landmarks can help bring hidden histories to light. For example, Tony Wood mentioned that LGBTQ+ historic sites often fall into this category, and initiatives like the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, of which Andrew Dolkart is a director, rely on the cultural significance of such sites in advocating for their preservation. Additionally, historic sites central to Black History in New York, are found in Columbia University’s interactive map and resource collection, Mapping the African American Past.

Cook reminded the audience that “the influence of New York’s preservation law is pervasive throughout the country.” Therefore, at a time when much of the nation’s underrecognized history is being raised up, cultural landmarks have rarely been more vital. In Ackerman’s summation, for those interested in preservation, “we have to fight the good fight if we want the city to reflect the full breadth of history and all the stories that can be told.”

This program was supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York City Department of Youth & Community Development in partnership with the City Council.