Today, New Yorkers are staying home in order to help stop the spread of coronavirus. The fact that our homes have become a first-line defense in the fight against infection adds this moment in New York City to a timeline, spanning well over 100 years, when the relationship between apartment living and public health has been heightened.

In 19th Century New York, public health officials noted that scourges like cholera and tuberculosis disproportionately affected the city’s densest neighborhoods, where working-class immigrant families lived in crowded tenements with little access to clean water, light or ventilation. By 1863, the Board of Health reported that mortality rates in the city’s tenement districts were triple those of the city overall.

Reformers like Lillian Wald, of the Henry Street Settlement, believed that illnesses like tuberculosis were “pre-eminently a disease of poverty,” which could “never be successfully combatted without dealing with its underlying economic causes: bad housing, bad workshops, undernourishment and so on.” Accordingly, reformers pressed the State to build health into the architectural fabric of New York, and won the passage of three successive Tenement Reform Acts in 1867, 1879 and 1901, which required health and safety precautions like fire-escapes, exterior-facing windows, indoor plumbing and courtyards.

The Upper East Side’s Yorkville neighborhood, which has an exceptionally rich and diverse history of immigration, became a veritable case study in public-health oriented housing reform. Not only were Yorkville’s early tenements built to reform specifications but also, private developers and philanthropists chose the neighborhood for a myriad of private “Model Tenement” projects that emphasized light, air and public health, seeking to redefine what low-cost urban workers housing could offer. Scroll on to join us for a virtual tour of health and housing in Yorkville!

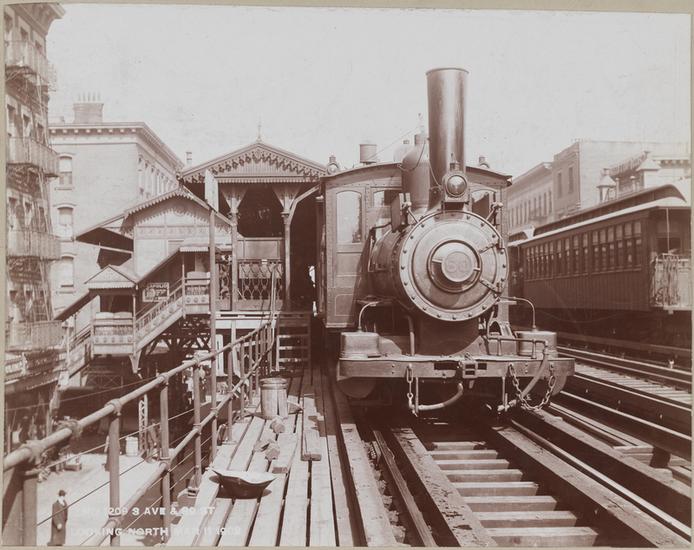

Yorkville’s tenements were built after new transportation transformed the neighborhood. No, we’re not talking about the Second Avenue Subway, we’re talking about the elevated lines that were completed on Third Avenue in 1878, and Second Avenue in 1880.

The El itself had been partly conceived as a public health measure. As early as the Civil War, reformers were concerned that population density in Lower Manhattan was contributing to overcrowded living quarters, and the spread of disease, especially among working-class residents. The Board of Health noted that cholera was disproportionately affecting the city’s Irish immigrant population because that community was “crowded together in the worst parts of the city.” When the first El, which ran along 9th Avenue, opened in 1869, it helped alleviate that density by carrying passengers to other parts of the city.

As it shuttled working-class residents uptown for the first time, the El brought a building boom, and helped solidify Yorkville’s identity as a polyglot, multi-ethnic melting pot. Yorkville’s tenements were considered a cut above those that immigrant workers had left down on the Lower East Side, and they were a bit different: Yorkville’s tenements were newly built, and they were largely constructed after the passage of the 1879 Tenement Law, which meant they featured exterior windows in every room.

High hopes that the 1879 Law would lead to a revolution in public health were seemingly dashed when developers began creating “Dumbbell Tenements,” which offered windows that looked out onto airshafts. Since those shafts were often filled with garbage, public health outcomes in dumbbell tenements were not so much improved. But, by 1901 “New Law” tenement legislation took on those airshafts by ruling that buildings needed courtyards for ventilation. The statue also required running water, and a toilet for each apartment.

These improvements were not the only concessions to the health of the city. Architectural style and ornamentation, too, were part of how architects and reformers sought to improve the life and health of the populace. Since tenement reform coincided with the “City Beautiful Movement,” which held that architecture, design and civic planning could uplift the city, many of Yorkville’s tenements were built in the prevailing architectural styles of the day, like Neo Grec, Romanesque and Renaissance Revival, featuring lovely design and ornamentation that enrich the streetscape.

Speaking of rich streetscapes, The Manhattan, a Queen Anne style apartment at the corner of 86th street and 2nd Avenue, cut an imposing figure when it was completed in 1880. It was the largest building in Yorkville, and according to the New York Times, is oldest surviving “large apartment house” in the city.

As Yorkville emerged as an immigrant enclave and center of progressive housing reform, private developers and philanthropists began to experiment with alternatives to the tenement for working and middle class residents. The Manhattan was a supreme early example of that alternative.

When it comes to development and philanthropy in Yorkville, the name Rhinelander stands out prominently. The Rhinelanders, whom you may recognize from the Hardenbergh/Rhinelander Historic District, acquired 48 acres of land along the East River in Yorkville at the turn of the 19th Century. Their contributions to the neighborhood included the Church of the Holy Trinity and the Children's Aid Society's Rhinelander Center, both on 88th Street.

The Manhattan was their first development in Yorkville. They enlisted Charles W. Clinton, who also designed the Park Avenue Armory, as architect. The Manhattan offered more light and air than one would find in a tenement, and boasted fewer tenants, larger accommodations, and luxuries like private hallways, fully equipped kitchens, and even dumbwaiters.

The fact that The Manhattan was not a tenement made it highly unusual for its time. Until the end of the 19th century, multi-family dwellings were considered exclusive to the poor; those with means owned or rented private homes, and co-ops did not exist in New York City until 1881.

The Manhattan sat right in the middle: a multi-family dwelling with enough concessions for light, air and ease that it was acceptable to the middle class. So how to describe it? At the time it was built, the Rhinelanders called it a “French Flat,” to give it the cache of the glamorous apartments in Paris, where multiple dwelling for the middle class was already de rigueur.

The success of the Manhattan inspired the Rhinelanders to create another French Flat in Yorkville known as the Kaiser and The Rhine, a pair of buildings constructed between 1886 and 1887, at 1716-1720 2nd Avenue. The Kaiser and The Rhine were designed by the firm of Lamb and Rich (who also designed Teddy Roosevelt’s home at Sagamore Hill, and the buildings in the Upper East Side’s Henderson Place Historic District.) The Romanesque Revival buildings were named to evoke German nobility, and appeal to Yorkville’s middle class German residents.

Today, The Manhattan and the Kaiser and Rhine buildings, conceived as alternatives to tenement housing are considered some of New York’s first “Modern Apartments,” setting a standard for health and convenience in the way we live now.

When it comes to the way we live now, perhaps no buildings in Yorkville are as attuned to our current moment as Cherokee Apartments (first known as the Shively Sanitary Tenements.) The Cherokee are a complex of four connected buildings between 77th and 78th Streets and between York Avenue and Cherokee Place.

The Cherokee Apartments were “Model Tenements” conceived by Henry Shively, head of the Tuberculosis Clinic at Presbyterian Hospital, financed by Mrs. Ann Harriman Vanderbilt, and designed by Henry Atterbury Smith. They were created to be the ideal curative environment for low-income tuberculosis patients and their families.

The complex, and all of its apartments, were filled with light and air. They sported triple hung windows, balconies for sleeping, open stairwells to mitigate the spread of disease, and ample courtyards and rooftop space for even more opportunities to catch a breeze. The goal was to “prove that accommodations may be constructed” which manage “to save human lives.” The Cherokee would prove that public health could be built directly into the urban environment.

When the complex opened in 1912, it was praised as the most “comfortable, sanitary and beautiful tenement” in the world, and lauded by the American Institute of Architects. Despite all the accolades, Henry Atterbury Smith considered The Cherokee a failure, because the complex was prohibitively expensive for working-class people, the very people they aimed to help. He told the New York Times in 1912 that while the Cherokee Apartments were “healthful and hopeful things to look upon,” they hadn’t reached their goal, because “beautiful apartments at more than $12 a month mean nothing to the family that can only afford to pay $10.”

Interestingly, the charitable trust that owned the Cherokee sold it to the City and Suburban Homes Company in 1924, which brings us to our next stop.

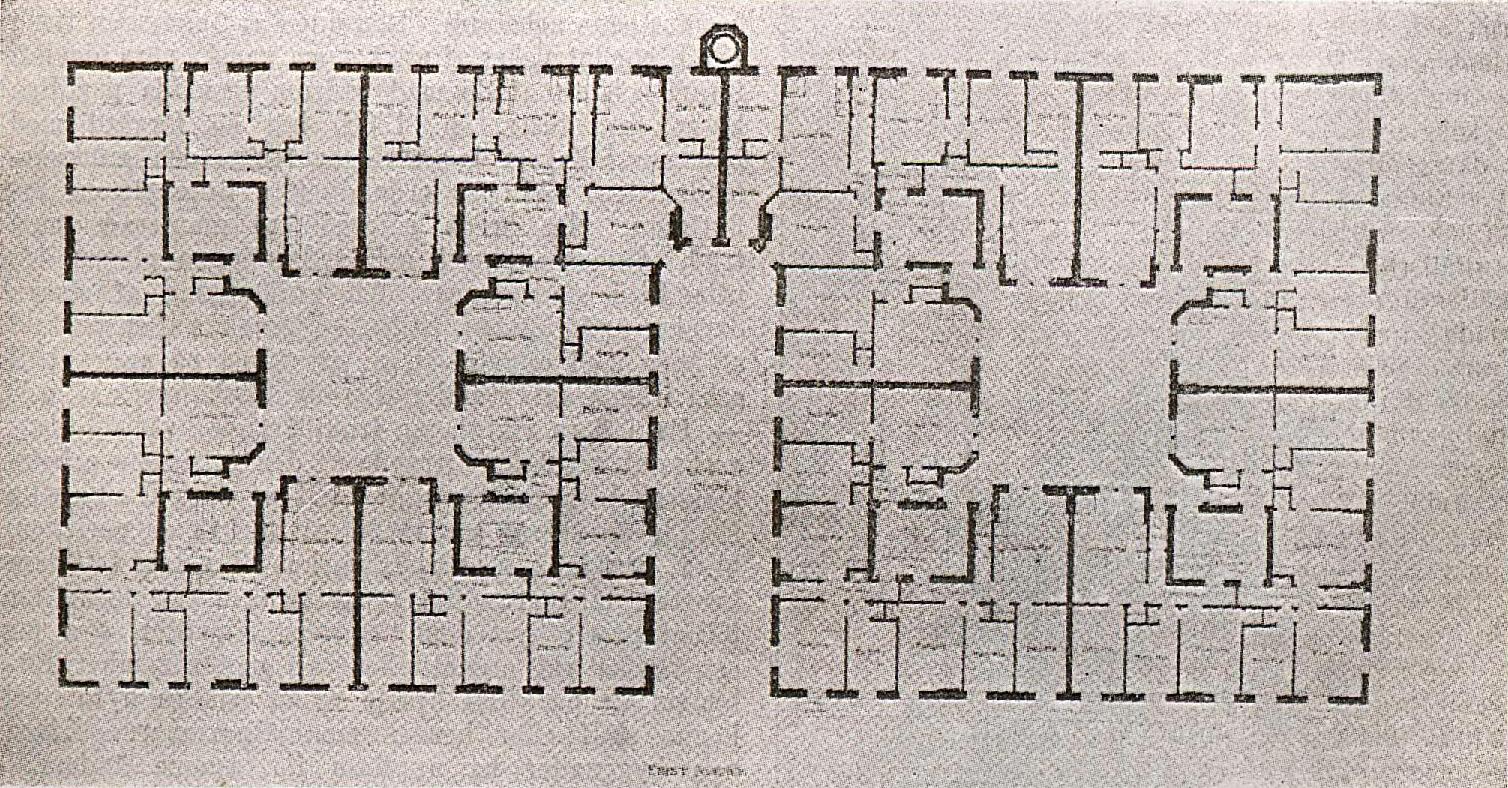

Just a block away from the Cherokee, at 79th Street and York Avenue, you’ll find City and Suburban’s York Avenue Estate, a block of Model Tenements completed in 1913. The Company also created The First Avenue Estate, a multi-building complex between First and York Avenues, and 64th and 65th streets built between 1898 and 1915.

With a stunning 1,300 units, The York Avenue Estate was the largest low-income housing development in the world when it was built, and “one of the most ambitious attempts in the history of New York to create viable housing for the poor.” Its sister complex, The First Avenue Estate, is the oldest surviving example of New York’s privately-financed, limited-dividend, Model Tenements.

The First and York Avenue Estates were experimental “light-court tenements,” 6-story walk-up buildings built around a series of private courtyards, which featured all the amenities inspired by health and housing reform, including wide stairwells and large windows and private bathrooms. The apartments offered tenants an abundance of light and cross-breezes, and were truly affordable in a way that the Cherokee apartments were not, so they became a haven for a diverse immigrant population seeking alternatives to traditional tenements. Residents hailed from all over the world, and the Estates helped them make, safe, comfortable, healthy new lives in America.

The Estates benefited a low-income immigrant population, but they were not charitable institutions. Instead, they were financed by some of New York’s most illustrious families, including the Vanderbilts, the Stokes and the Goulds. By limiting their profits from these complexes to 5%, these builders sought to find a “middle ground between pure philanthropy and pure business,” keeping the homes within the reach of working New Yorkers while proving that well constructed low income housing could turn a profit. They hoped such proof would convince other private developers to raise the standard of their own low-income housing, so that the cramped, dark tenement would be a thing of the past.

These historic experiments in healthful housing continue to serve as relatively affordable options within the neighborhood. They also offer a historic model to inform and inspire current affordable housing efforts. Originally built to offer their tenants improved living conditions, light, air and a greater sense of place within the city, these buildings proved that human-scale development and community-oriented planning could immeasurably enrich the city. As these buildings continue to enrich our streetscape, FRIENDS is proud to continue our work towards preserving the architectural legacy, livability and sense of place of the Upper East Side.

Written by Lucie Levine, FRIENDS Public Programs Consultant, and founder of Archive on Parade.

This program was supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York City Department of Youth & Community Development in partnership with the City Council.