FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts was founded in 1982 to preserve and celebrate the architectural legacy, livability, and sense of place of the Upper East Side.

But what did the Upper East Side look like in the 1980s, when FRIENDS appeared on the scene?

In honor of Jane’s Walk 2021, we are thrilled to debut our collection of local architectural photography from that decade, and share highlights from our 80s archive, documenting the buildings and streetscapes of the Upper East Side.

Through the work of dedicated organizations like FRIENDS, much of the Upper East Side is protected within historic districts, or as individual landmarks.

But, landmark designation does not create stasis in our communities, nor would we want it to. Scroll through the following 10-stop tour to see how much our landmarked neighborhoods have changed since the 1980s!

25 East 61st Street

In the ‘80s, 25 East 61st st. was home to B. Harris & Sons, jeweler to the stars!

25 East 61st street is the rear extension of 673 Madison Avenue, an Italianate brownstone built in 1871 by architect John G. Prague as part of a project for the developer John McCool which included a row of 5 brownstones on Madison Avenue, and 17 houses on 61st street.

B. Harris & Sons was a family-owned, fine-jewelry business established in New York City in 1898 by B. Harris, a Russian immigrant who had been an artisan to Czar Alexander III.

Having pilfered a precious stone from the royal workbench to pay for passage out of Russia, Harris and his wife fled the empire, walking across an ice bridge to Finland. The Harrises arrived in New York via London, and by 1926, B. Harris & Sons became the first retail jewelry store on West 47th Street.

Harris’s sons Charles and Nathan shepherd the store to East 61st st., where it became one of the city’s leading jewelers (The July 12, 1976 issue of New York Magazine lists clients including Gloria Steinem, Helen Hays, Richard Rodgers and Marion Javits.)

B. Harris and sons closed in 1991, when Nathan Harris retired.

Interestingly, 25 East 61st Street is currently home to the estate jewelers Stephen P. Kahan & son.

6 East 63rd Street

Home to the New York Academy of Sciences for more than 50 years, this mansion of 63rd Street is now vacant!

Ah, the spoils of Big Baking Powder!

This neo-Italian Renaissance palazzo at 6 East 63rd Street was built between 1919-1921 as a private mansion for William Ziegler Jr., heir to a vast baking powder fortune, and his first wife, Gladys.

Though the house was grand, the marriage was not, and when William and Gladys split in 1926, they sold the house theater impresario David Belasco, who hoped to turn the space into a hospital exclusively for actors.

The hospital never came to fruition, and the house changed hands again in 1929. That year, it was sold to Norman Bailey Woolworth, 3rd cousin of the five-and-dime king.

In 1949, Woolworth donated the house to the New York Academy of Sciences, and the building was reconfigured as office space for that organization.

The Academy made its home in the building until 2005, when it sold the property to the billionaire Leonard Blavatnik for $31.25 million, and moved downtown to 7 World Trade Center.

But Blavatnik bought the building as an “investment” rather than a residence, and it has been vacant since the sale!

In the ‘80s the corner of Lexington Avenue and 66th Street was at the forefront of the Body Positivity Movement, as the home of the Forgotten Woman, the original plus-size luxury boutique!

Forgot about The Forgotten Woman?

This shop, at 888 Lexington Avenue, opened in 1977, was the original store in what grew to be a chain of more than 30 plus-size boutiques across the United States.

The Forgotten Woman was founded by Nancye Radmin, a pioneer in plus-size fashion, who died in 2021.

Radmin founded the store because she was “laughed out of stores” in Manhattan when she went looking for finely made, fashionable clothes in plus sizes. She knew that plus-sized women were being ignored by the fashion industry, and began stocking her boutique with clothing she would like to wear.

Radmin even worked directly with 7th Avenue manufacturers and top designers like Oscar de la Renta to make clothing specifically for her stores.

This location closed in 1999 when the chain went into bankruptcy.

50 East 68th Street

In the ‘80s, the rowhouse at 50 East 68th street was so stripped down, the LPC listed its style as “none.” In 1997, the Council on Foreign Relations rebuilt the lot from the ground up in gracious limestone, completing its quartet of adjoining buildings on the block.

If this black and white building at 50 East 68th Street strikes your eye as a high contrast to the 19th-century rowhouses surrounding it, you are not alone.

In fact, this building seemed so out of place among its neighbors that in 1995 the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), which already owned numbers 56-60, 54, and 52 on East 68th, bought the building and decided to reappoint it in classic limestone.

The reconstruction took place in 1997, and delivered the facade we see today. The project allowed the CFR to expand and reconfigure its office space.

2021 marks the Council on Foreign Relations’ centennial. The CFR originally rented rooms on West 43rd St., but moved to East 68th Street in 1945, when Harriet Barnes Pratt donated the Pratt mansion at 68th street and Park Avenue to the organization. Her husband, Harold Irving Pratt, the youngest son of the oil magnate Charles Pratt, had been a CFR member.

The Pratt House, No. 58, was built in 1919 by the society architects Delano & Aldrich, and was expanded in 1954. The council continued purchasing space on 68th Street until it completed the quartet it owns today.

167 East 69th Street

In the ‘80s, this converted carriage house was home to The Sculpture Center. Since 2001, it has been a private residence!

Today, 167 East 69th Street is a 25-foot-wide, 3-story neo-Georgian home, which traded hands most recently in March 2020 for $11 Million.

But, this structure began its life as a stable, completed in 1909 by the architect Charles Birge, who was best known for his Bankers Trust building on 57th and Madison, and for creating William Randolph Heart’s quintuplex on Riverside Drive.

The building’s life as the Sculpture Center began in 1948, when that organization - founded as The Clay Club by sculptor Dorothea Denslow in Crown Heights in 1928 - purchased the 69th St. stable and turned it into an exhibition space and studio school.

The transition from stable to sculpture school was led by the artists themselves, who eventually created a gallery space on the first floor and workshops and studio space on the upper floors.

The school stood out as the city’s only institution devoted entirely to sculpture, offering studio space to both amateur and professional sculptors. Alumni of the 69th Street center include Louise Nevelson, Isamu Noguchi, and Rube Goldberg.

The Sculpture Center controversially sold the building in 2001 for $3.65 Million, and entirely jettisoned the school in favor of contemporary gallery space in Long Island City which it occupies today. The LIC space does not offer classes.

The buyers in 2001 turned out to be the novelist Ann Brashares, who wrote The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, and her husband, the painter Jacob Collins. When the pair remodelled the carriage house, they kept an art studio on the ground floor.

Brashares sold the building in 2020, and it remains a private residence.

966 Lexington Avenue

In the ‘80s, 964-966 Lexington Avenue was home to Dietz Market, a specialty food emporium, and Hennor Jewelers & Clockmakers, a timepiece repair shop. Today, it’s home to FRIENDS!!!

Originally built in 1872 as a pair of Italianate brownstones, 964-966 Lexington Avenue, between 70th and 71st Streets, was converted into apartments with ground-floor retail space in the late 1920s.

By the 1980s, both Dietz Market and Hennor Jewelers & Clockmakers had been serving customers at this location for decades.

A 1964 New York Times Article, profiling a family of Vermont cheesemakers, notes that the cheese in question could be purchased at Dietz Market at 964 Lex. “Costs range,” the paper wrote, “from about $5.95 for a four and one‐quarter pound cheese sampler to $6.50 for a six and one‐half pound deluxe cheese sampler.”

The Times went on to note, in 1992, that proprietor and clocksmith Norman Steinkritz had been fixing timepieces at 966 Lexington Avenue for more than 40 years.

For our part, FRIENDS moved to 966 Lexington Avenue in 2012, when we celebrated our 30th Anniversary!

9 East 72nd Street

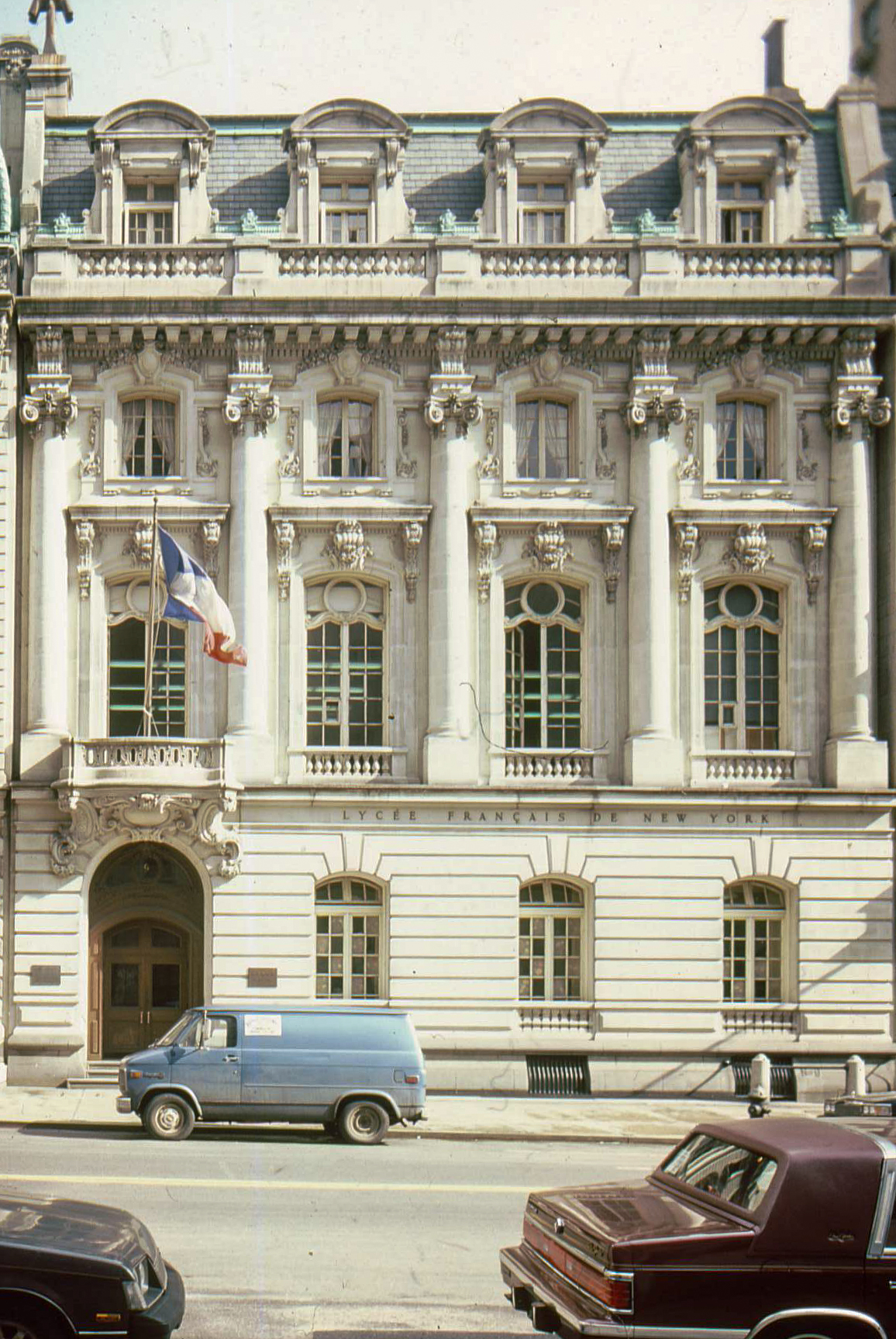

In the ‘80s this grand gilded age mansion was home to the Lycee Francais. Since 2002, it has returned to its roots as a single-family home, owned by the Emir of Qatar.

The French flag flying from 9 East 72nd Street looks right at home on this exuberant Beaux-Arts French Renaissance facade. But, this building was not built for French patrons.

Though it housed the Lycee Francais from 1964-2002, this confection on 72nd was actually designed by Carrere and Hastings (who designed the New York Public Library), and completed in 1896, for Henry T. Sloane, a carpet magnate, and his wife Jessie.

The pair divorced in 1899, and within 5 hours of the decree, Jessie had remarried! This time, she wed Perry Belmont, and the newlyweds moved down to Washington.

The cuckolded Sloane also left the 72nd Street home. He built a new house for himself and his daughters at 18 East 68th Street, and rented 9 East 72nd to Joseph Pulitzer, who moved in with his family of 6 and a staff of 17 servants!

The house changed hands between two millionaires and a religious institution until it was purchased by the Lycee Francais in 1964.

On the strength of its history and architecture, the Henry and Jessie Sloane house was designated an individual New York City landmark in 1977.

The Lycee sold it to the Emir of Qatar in 2002 for $26 Million.

In the ‘80s, the carriage house at 161 East 73rd St was an innovative music and movement school. Today it is a private residence!

161 East 73rd St is an individual landmark, designated in 1980.

Though this building sits outside the Upper East Side Historic District, it is part of the National Register of Historic Places “East 73rd Street Historic District,” which includes 15 individually landmarked carriage houses lining both sides of 73rd Street between Lexington and 3rd Avenues.

The 73rd Street carriage houses were built by prominent architects including Richard Morris Hunt, for wealthy Upper East Siders who lived in mansions to the west.

161 and 163 East 73rd Street were built as a pair in the Romanesque Revival Style, and completed in 1897 for the dry goods merchant William Tailer. They featured stables on the ground floors and grooms’ apartments upstairs.

In 1901, Tailer sold 161 to John Woodruff Simpson, senior partner of the law firm Simpson, Thatcher and Bartlett; Simpson’s art collection is now part of the National Gallery.

In 1907, oil scion and ardent philanthropist Edward S. Harkness, purchased No. 161. Two years later, he put his architect, James Gamble Rogers - who had also designed the spectacular Harkness House on 75th Street and 5th Avenue - to work modernizing the carriage house. Those alterations included turning the stables into a garage, and putting a squash court on the second floor!

After Mary Harkness’s death in 1950, the carriage house was sold to the Dalcroze School of Music.

The Dalcroze School was a music school and teacher-training institute which followed the teaching philosophies of Swiss educator and composer Emile Jaques-Dalcroze.

Dalcroze combined physicality with music, teaching both music theory and body movement. In 1902, he established a school in Germany, and musicians including Paderewski and Rachmaninoff, as well as dancers including Martha Graham and Ted Shawn, came to study with him.

Dalcroze first introduced his methods to the United States in 1911, and founded the Dalcroze School in New York in 1915.

The school remained at 161 East 73rd from 1950 until 1993, when it closed upon the retirement of its director, Dalcroze’s student Hilda Schuster.

In 1994, the building was sold, and today it is a private residence.

1014 Fifth Avenue

In the ‘80s 1014 Fifth Avenue was home to Goethe House, a German Cultural Center sponsored by the German Government. Today, Germany's Government still owns the building, and sponsors TenFourteen Space for Ideas, an American non-profit dedicated to transatlantic cultural partnerships, which launched in 2017 and is housed in the building!

This 1906 Fifth Avenue mansion between 82nd and 83rd Streets is interesting because it was not built specifically for a wealthy denizen of “Millionaire’s Row.” Instead, it was built on spec by William and Thomas Hall, who advertised it as being at the cutting edge of modern metropolitan mansions. It was fireproof! It had an elevator!

Eventually, No. 1014 found a buyer: The banker James F. Clark. Clark and his wife Edith moved in the following year and lived at the building intermittently until 1926. They decamped to Park Avenue, and sold the house to their next-door neighbor, James W. Gerard and his wife Mary.

Gerard had been the former (and the final) American Ambassador to Imperial Germany.

After Mary died in 1956, the house’s diplomatic relationship with Germany did not end.

In 1954, the West German Ambassador began plans for a German Institute in New York that would foster warm cultural relations between the United States. The following year, Goethe House was chartered, and the organization bought 1014 Fifth Avenue in 1959. The Goethe Institute opened at No. 1014 in 1961, and stayed in the building until 2008. (Today, it’s housed on Irving Place)

The building sat vacant for nearly a decade until TenFourteen Space launched in 2017.

German Heritage has had a profound influence on the development of the Upper East Side’s Yorkville neighborhood, which is where this tour will end. At our final stop, ‘80s era photos of the Church of the Holy Trinity help show the state of the building at that time, which inspired the president of our board, Franny Eberhart, to take up her first preservation fight!

In the 1980s, The Church of the Holy Trinity, an 1899 individual landmark, was falling into disrepair. At that time, our board president, Franny Eberhart, began her work as a preservationist here, advocating to restore the church!

This beautiful French Renaissance church was commissioned in 1897 by Serena Rhinelander, and completed in 1899 by Barney & Chapman, whose ecclesiastical work included the chapel of Grace Church at 14th Street and First Avenue.

Serena Rhinelander, a descendant of the Rhinelander Family which had owned vast tracts of Yorkville since the 17th Century, conceived and built Holy Trinity as a gift to the neighborhood, and as a memorial to her father and grandfather, who had developed much of the neighborhood.

Writing about the Rhinelanders’ role in the neighborhood, Eberhart notes, when Holy Trinity opened in 1899, “it was known as a ‘settlement church’ aiming to ‘cultivate the best in [humanity], physical, mental, social, and spiritual. It is not content to preach only to the soul…but with its clubs and societies seeks to help and elevate the social conditions amongst its members and the neighborhood in which it stands.’ In a neighborhood full of religious institutions established by particular ethnic groups, Holy Trinity was unique in that it was open to people of all national origins.”

Today, we continue to advocate for spaces like Holy Trinity and to preserve and celebrate the architectural legacy, livability, and sense of place of the Upper East Side.