The Upper East Side’s three landmarked armories might be the most “commanding” structures in the neighborhood. Among New York’s earliest landmarks, these fortified urban fortresses were built to store arms and to provide training and social space for local regiments whose members served in every major U.S. conflict from the War of 1812 through The Second World War. More recently, these structures have been transformed into schools, park facilities and art spaces. Today, they offer a slice of local history and an impressive catalog of ideas for adaptive reuse. As the conversation continues around reorienting our city’s martial elements toward the communities they serve, the evolution of our neighborhood’s armories reminds us that historic preservation is a tool both for honoring the past and for enriching the present. Scroll on to learn more about the Upper East Side’s armories.

You may have noticed that FRIENDS has recently begun publishing a series of in-depth pieces focused on local history and preservation. We have received positive feedback and community support for these “deeper dives,” and we are happy to announce that will be offering them regularly as part of a new series called “East Side Extra!” Each piece in the series will offer a closer look at a lesser-known area of local history or advocacy, and will be housed as a dedicated collection on our website, where you can access it at your convenience. You can find all previous installments in the series there, and we’re happy to share a new installment here!

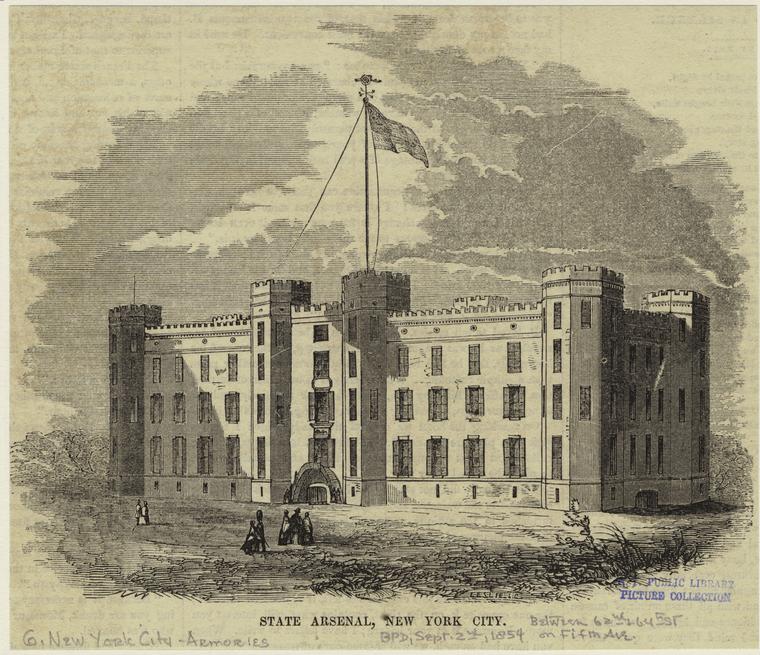

Begun in 1847, and completed in 1851, the Arsenal in Central Park is the oldest armory on the Upper East Side, and one of just two buildings standing in Central Park that predate the park itself. Designed in what the Landmarks Preservation Commission calls the “early English manorial fortress style,” by Martin E. Thompson (a cofounder of the National Academy of Design), the Arsenal was created to “house and protect the arms of the state,” and served as the headquarters for New York’s Seventh Regiment National Guard, from 1853-1857.

The Arsenal served as an armory for just six years, before it moved on to its next act in 1857 when the City purchased the building, and the land beneath it, from the State of New York to be incorporated into the nascent Central Park. Upon becoming Park property, all arms and munitions were removed from the building, and the Arsenal was transformed into headquarters for both Central Park’s administrative offices, and Manhattan’s 11th police precinct.

The building’s relationship with the Central Park Zoo, which continues to this day, began in 1859, when animals began to arrive as gifts or loans from notable figures including P.T. Barnum, August Belmont and General William Tecumseh Sherman, and a menagerie was developed in and around the Arsenal.

In 1869, the Arsenal pivoted to dinosaurs, becoming the first home of the American Museum of Natural History. The Natural History Museum operated on the second and third floor of the Arsenal for eight years, during which time the British paleontologist B. Waterhouse Hawkins maintained a studio in the building for reconstructing dinosaur skeletons.

In 1870, the Arsenal underwent the first of three major restorations. That year, Jacob Wrey Mould (who also designed Bethesda Terrace, Belvedere Castle, and the fountain in City Hall Park) remodeled the building’s interiors. Though the Parks Department considered demolishing the building in 1916, it was instead remodeled in 1924, and again in 1934. That time, Robert Moses commissioned a series of Work Progress Administration murals for the building’s lobby, still visible today, which depict the city’s finest parks and recreation facilities.

That’s not the only art in the building. The Arsenal is also home to a gallery space for exhibits dedicated to “the natural environment, urban issues and parks history,” and serves as headquarters for the NYC Parks Department, City Parks Foundation, the Historic House Trust, and the New York Wildlife Conservation Society.

The Seventh Regiment Armory was built 1877-1878 as a headquarters for New York State’s Seventh Regiment National Guard, best known by its nickname, “The Silk Stocking Regiment,” owing to its socially prominent membership, including members of the Vanderbilt, Roosevelt, Livingston, Beekman, Rhinelander, Schermerhorn and Harriman families. The building’s architect, Charles W. Clinton, a student of Richard Upjohn and a premier Gothic Revivalist, was also a veteran of the Seventh Regiment.

The Regiment was founded in 1806, as a unit of the New York State Militia, and members served in the war of 1812, deployed to protect the City’s harbor forts. Throughout the 19th Century, the Seventh Regiment was called to quell a number of riots that broke out in New York City, including the 1849 Astor Place Riot, the 1857 Police Riot, and the 1863 Draft Riot. During the Civil War, the Seventh Regiment was the first to answer President Lincoln’s call to defend Washington, D.C., and half the Regiment served with other companies in the Union Army. Six soldiers won the Medal of Honor for their service. The Regiment was federalized during WWI as the 107th infantry, which saw combat in France, and in WWII as the 207th Coast Artillery which served in Europe and the Pacific.

The Seventh Regiment Memorial, designed by John Quincy Adams Ward, stands in Central Park at West 69th Street, a site selected by Frederick Law Olmsted. The memorial, dedicated in 1874, was paid for by officers and members of the Regiment. The Armory stands as the last surviving privately financed Armory in the United States.

Given its wealth and social prestige, the Seventh Regiment Armory served as both a drill-hall and an extremely opulent social club. The interiors of the Veterans Room and the Trophy Room were designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany, in consultation with Stanford White, and feature beautiful examples of Tiffany glass, and hand-carved wood. Architectural historian Andrew Dolkart calls these rooms, “some of the finest surviving 19th Century rooms in America.” Originally a three-story structure, the fourth and fifth stories were added between 1909 and 1914.

The Armory is also notable for its 55,000 square foot drill-shed, which is one of the largest unobstructed interiors in the city, and is, according to the World Monuments Fund, “the oldest extant ‘balloon shed’” in New York. The National Indoor Tennis championships were held in the drill-shed from 1900-1963, and the Knickerbocker Greys, the oldest after-school program in the nation, has used the drill-shed since 1902.

Since 1996, the Lennox Hill Neighborhood House has managed a Women’s Mental Health Shelter at the Park Avenue Armory. Since 2006, the non-profit Park Avenue Armory Conservancy has run a full slate of arts programming from the building, and partnered with nine New York City schools for arts education programming.

The Squadron A Armory was built in 1895, and its Madison Avenue frontage was landmarked in 1966 as part of a dramatic, mid-demolition emergency action by the LPC. Based on what the Landmarks Preservation Commission calls, “twelfth century French prototypes” and “American Inventiveness,” the Squadron A Armory was designed as “an excellent example of a medieval castle,” by John Rochester Thomas (who also designed New York’s Surrogates Courthouse – now home to the Municipal Archives).

This was Thomas’s second armory within the square block. He had also designed the Eighth Regiment Armory (demolished 1966), which was erected between 94th and 95th streets facing Park Avenue, in 1888-1890. His Squadron A Armory directly abutted the Eighth Regiment from the west, facing Madison Avenue.

Established in 1884, Squadron A was originally a social and equestrian club for young men who called themselves the New York Hussars, a reference to Medieval and Renaissance Central European mounted cavalry units. Appropriate for a cavalry unit, the armory included a riding ring and about 100 horse stalls. The Hussars officially became a unit of the New York State National Guard in 1889 and were mobilized in the 19th century for the Spanish-American War, and against local labor strikes. In WWI, Squadron A fought as the 105th Machine Gun Battalion at Flanders and Ypres. In WWII it was incorporated into the 101st Cavalry.

Like their compatriots in the Seventh Regiment, Squadron A also drew from the upper echelons of New York Society. For example, the prominent New York architect C.P.H. Gilbert, who designed many of the Upper East Side’s most opulent Gilded Age mansions, including the Fletcher/Sinclair Mansion (now the Ukrainian Institute) and the Warburg Mansion (now the Jewish Museum), was also a Squadron A member.

In 1920, Squadron A expanded into the Eighth Regiment Armory and combined the two structures to create an especially large riding ring. With more space, Squadron A expanded their social facilities, and became famous for Saturday polo matches followed by black tie soirees. According to the New York Times, 60 polo horses were still stabled there as late as 1962.

By the mid-1960s residents of Yorkville and East Harlem began demonstrating in favor of school buildings and middle-income housing on the site, and the State granted the Armory to the Board of Education for I.S. 29 (now Hunter College High School). The American Institute of Architects and the Municipal Art Society submitted proposals to build within the Armory’s existing structure, which were rejected in favor of a new building. As the Park Avenue side of the Armory was demolished to make way for the school, neighborhood advocates prevailed upon the LPC to landmark the surviving Madison Avenue facade and it was designated in 1966. Ultimately, to design a new building the Department of Education hired Morris Ketchum, Jr., who had served as president of the Architectural League of New York, the Municipal Art Society and The American Institute of Architects, and later became vice chairman of the LPC. For the new school building, Ketchum designed a modern red-brick fortress, completed in 1969, that draws inspiration from the remnant of the surviving Armory.

The fate of the Squadron A Armory showed a community commitment to both preservation and adaptive reuse on the Upper East Side, which remains instructive to us today. As each of our neighborhood’s armories have transitioned into spaces devoted to arts, education and municipal services, they stand out as blueprints for how we can preserve our city’s past while also meeting the current needs of our moment.