Who is the Bridge and Tunnel crowd? In more quotidian times, that moniker might call to mind tourists from New Jersey. Currently, the crowd in question might be New Yorkers themselves: Over the past several months, many New Yorkers have sped across these spans on their way out of the city. At the same time, subway-wary city-dwellers have also streamed across New York’s bridges, and through its tunnels, making what would ordinarily be public transit trips by foot, bike or car. Whether you’re in-town or out-of-town, this is a bridge and tunnel moment for New York City. Since the pandemic has redefined our relationship the city’s iconic modes of ingress and egress, let’s take this moment to recognize the bridges and tunnels that carry us in and out of the Upper East Side. Scroll on for a bridge and tunnel history of the neighborhood.

Let’s begin by Feelin’ Groovy, on the 59th Street Bridge. The cantilevered span, now officially known as the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge, was the first bridge to link Manhattan and Queens. Originally called the Blackwell’s Island Bridge (in reference to the original name for Roosevelt Island), the bridge opened to traffic on March 30, 1909, after a construction process that lasted eight years.

Work on the bridge began in 1901, but picked up in earnest beginning in 1902, when Mayor Seth Lowe appointed the civil engineer Gustav Lindenthal as the city’s first Commissioner of Bridges. In that capacity, Lindenthal worked on several East River spans, including the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges, but he was particularly influential in the design of the Queensboro and Hell Gate Bridges; he teamed up on both those projects with the Brooklyn-born architect Henry Hornbostel. Though Hornbostel, who had studied at L’École de Beaux-Arts, is responsible for the Bridge’s more fanciful elements, including its masonry towers, the span’s dominant aesthetic is industrial, which earned the bridge the nickname “Hornbostel’s Erector Set.”

At 7,449 feet, the Queensboro is the longest of the East River bridges, and the only one designed in the cantilever style (all the others are suspension bridges). To create such a long span, it took 75,000 tons of steel, provided by the Pennsylvania Steel Company. But that steel did not go up without comment: steel workers of the 40 Local union branch briefly considered blowing up the 59th Street Bridge between 1907-1908, though they ultimately abandoned the explosion when it became clear that firemen at work beneath the bridge would be put in danger, and even killed, by the blast.

When it was finally opened to the public in 1909, the 59th Street Bridge had some exceptional features, which are now lost to history, and others which are with us to this day. For example, the bridge originally supported a trolley line, which functioned until 1957, and ran across the bridge to Queens. If you didn’t want to go all the way inter-borough, and wanted instead to stop at Roosevelt Island, the bridge still had you covered. Originally, it sported an elevator that would ferry pedestrians and vehicles down to Roosevelt Island (the car elevator was put out of service in 1970, though the pedestrian model functioned until 1973). Given that the bridge was landmarked in 1974, some of its defining architectural features are still with us, including the exceptional Guastavino tiled ceiling, which now forms the ceiling of the Bridgemarket shopping center created from the enclosure of the area under the bridge on its Manhattan side.

The 59th Street Bridge might not have that Roosevelt Island elevator anymore, but Upper East Siders have an even more exciting option for getting to the Island, and that’s the cherry-red Roosevelt Island Tram, which the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation calls “the most modern aerial tramway in the world.”

The tram makes the 3,140 foot trip between 59th Street/2nd Avenue and Roosevelt Island in less than three minutes. Climbing up to 230 feet high during that trip, the tram also offers some of the best views in New York (and particularly nice views of the 59th street bridge, which it glides serenely beside).

The tram opened in May 1976, as a temporary mode of transport for New Yorkers awaiting the completion of the Roosevelt Island F Train station. By the time the station opened in 1989, the tram was too popular to be abandoned, so it carried on service uninterrupted until 2010, when it shuttered for a complete renovation.

That $25 million modernization project, carried out by the French company Poma, completely redesigned the tram, upgrading it from a single-haul system to a dual-haul system, which lets two separate cars operate independently at the same time. The renovation also rendered the tram completely handicap accessible.

Though the tram is owned and operated by the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation, it shares revenues with the MTA, and thus both follows the Metrocard fare structure, and offers transfers to New York City Transit subways and busses.

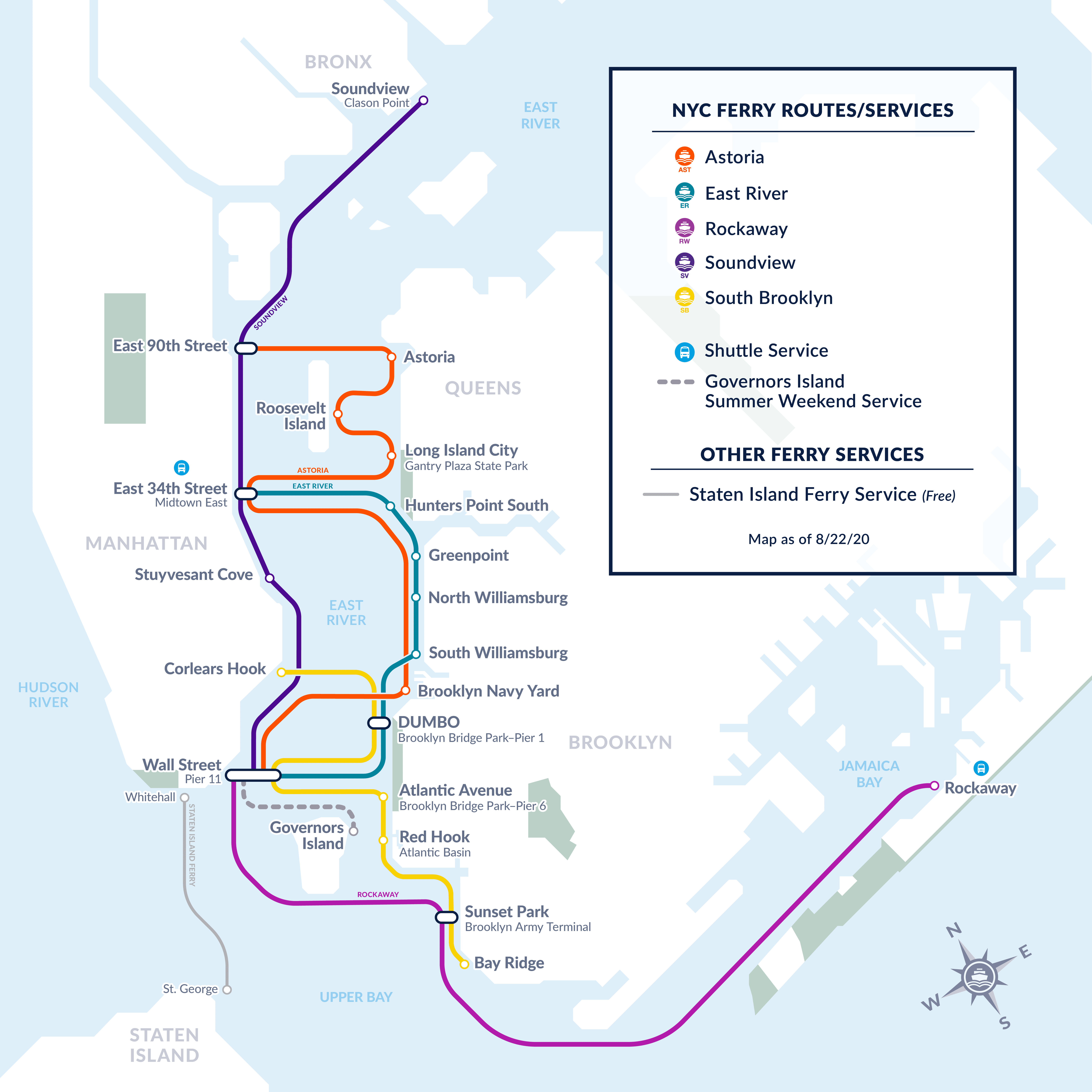

The Upper East Side’s newest mode of transit across the East River is ferry service. The NYC Ferry, operated by Hornblower, opened its 90th Street pier at the FDR Drive on August 15, 2018. The Yorkville ferry landing offers service along the system’s “Soundview Route,” which connects the Upper East Side with Soundview in the Bronx, and with 34th Street, Stuyvesant Cove and Wall Street in Manhattan. Most recently, after a petition launched in May of last year by the Old Astoria Neighborhood Association and spearheaded by the Durst Organization, a development firm, the "Astoria" line was expanded to include 90th Street Landing. The distance between the Astoria and 90th street is just 1,515 feet, and now the journey between the neighborhoods that can take up to an hour by train can be made in less than five minutes! The new stop also offers Upper East Siders direct access to all of the stops on the Astoria route, including Gantry Plaza State Park in Long Island City, and the innovation hub at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

While ferry service has plied the East River since at least 1642, the genesis of what is now NYC Ferry began in 2011, as the NYHarborWay initative, supported by the NYC Department of Transportation. By June of that year, NY Waterway was running a 7-stop East River ferry loop between 34th street and Hunters Point. Due to its popularity, and to Hurricane Sandy’s devastation of subway links in Queens, particularly in the Rockaways, ferry service became a focus for transit advocates. Funding lagged in 2014, and the service closed, but Mayor de Blasio proposed a city-wide ferry service in 2015, which launched as NYC Ferry on May 1, 2017.

Because NYC Ferry is built and funded by the New York City Economic Development Corporation, the price of a ride on the ferry is just $2.75, equal to subway fare. But, the service is not run by, or in concert with, the MTA, so it does not accept Metrocards, or offer free transfers to other modes of public transport. But, free transfer tickets are available between routes within the ferry system itself.

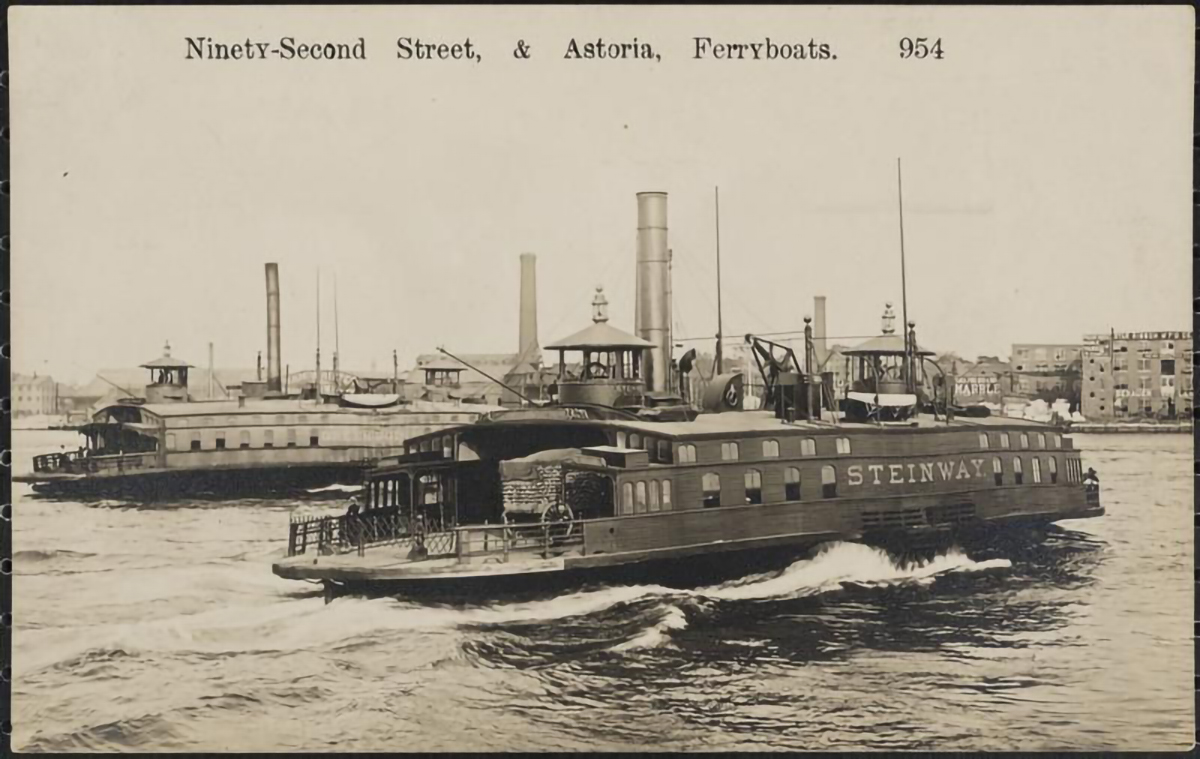

The call for a direct ferry link between Yorkville and Astoria has historical precedent. According to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, a ferry between 86th Street and Astoria opened as early as 1801. The American Institute of Architects holds that a new ferry landing opened at 92nd Street in 1867, and the ferry left from there to make the trip to Astoria.

William Steinway moved his piano factory to Astoria in 1870 “to escape the machinations of the anarchists and socialists” in Manhattan who were “continually breeding discontent among our workmen and inciting them to strike." In addition to putting a river between Steinway and labor politics, Astoria also offered the space and lumber necessary to expand the firm’s operations. (The factory still operates from Astoria, and celebrated it 600,000th piano in 2015).

As FRIENDS wrote in our book Shaped by Immigrants: A History of Yorkville, many of the people employed at the Steinway factory were skilled German craftsman living in Yorkville. These workers commuted to the factory, via the 92nd Street Ferry. That ferry officially came to be known as the Steinway Ferry, but was colloquially known as the “Piano Ferry.”

That ferry was brought under municipal control by Mayor Hylan in 1920, because it had been losing money since the opening of the Queensboro Bridge. (Hylan liked municipal control of mass transit – he was the mind behind the Independent (IND) subway, which was the first municipally-run subway system). The ferry was run municipally until 1936, when Robert Moses decided that the Triborough Bridge made it redundant, and he razed both the 92nd street slip and the ferry house to make room for the Triborough’s FDR Drive approach.

Whether you’d rather drive across the bridge, sail aboard the ferry, or glide along the tram, the Upper East Side offers some of the city’s most beautiful, and unique ways of getting in and out of town.